Yahaya, the young man who changed my view of the world

Petra Bošnjak, the student of physiotherapy at Alma Mater, joined the student project “Physiotherapists without Borders” expedition to Ghana. She describes the experience as unforgettable, sharing her impressions in the letter below. Worth reading!

I decided to do an Erasmus+ traineeship as a member of a student humanitarian mission in Ghana, Africa. It was a unique experience to learn about physiotherapy in one of the poorest parts of West Africa, where crisis is part of everyday life and where traditional medicine is often practiced due to a lack of resources and education.

During the traineeship, she developed cultural competence, improvisation, and adaptability due to the lack of physiotherapy equipment. The guidance of the mentor from the Larabanga Health Center was crucial in adapting to the local environment.

It was a precious experience for me as my goal is eventually to work for international humanitarian organizations in areas affected by conflicts or disasters.

As a team of 5 volunteers, we worked in the Larabanga clinic and the field. During home visits, we encountered more severe cases of physical impairment where people had no access to therapy or rehabilitation other than traditional medicine, which can often be harmful.

One of the cases we encountered was Yahaya, a young man who has endured unspeakable physical suffering for the last ten years caused by a childhood accident when he fell from a tree. He broke both ends of his femur and underwent surgery, returning to a distant hospital only once for a check-up.

His mother, Mariam, a single mother, cared for him as best she could, but a lack of resources and the severe health challenges she faced on her own meant that Yahaya's injury was not adequately cared for.

Between the age of 10, when the accident happened, and the age of 20, how old Yahaya is now, his young body grew along with a silent infection in his bone marrow. Poverty often means a lack of hygiene and also lack of education. His loving mother turned to traditional medicine to help him, thinking hot water would clear the infected open wounds. It was a culture shock for us, but we tried not to judge it and to reeducate them about this harmful practice. Yahaya had to stop school for the last five months since his health deteriorated, and he could not study due to the pain and unhealed wounds.

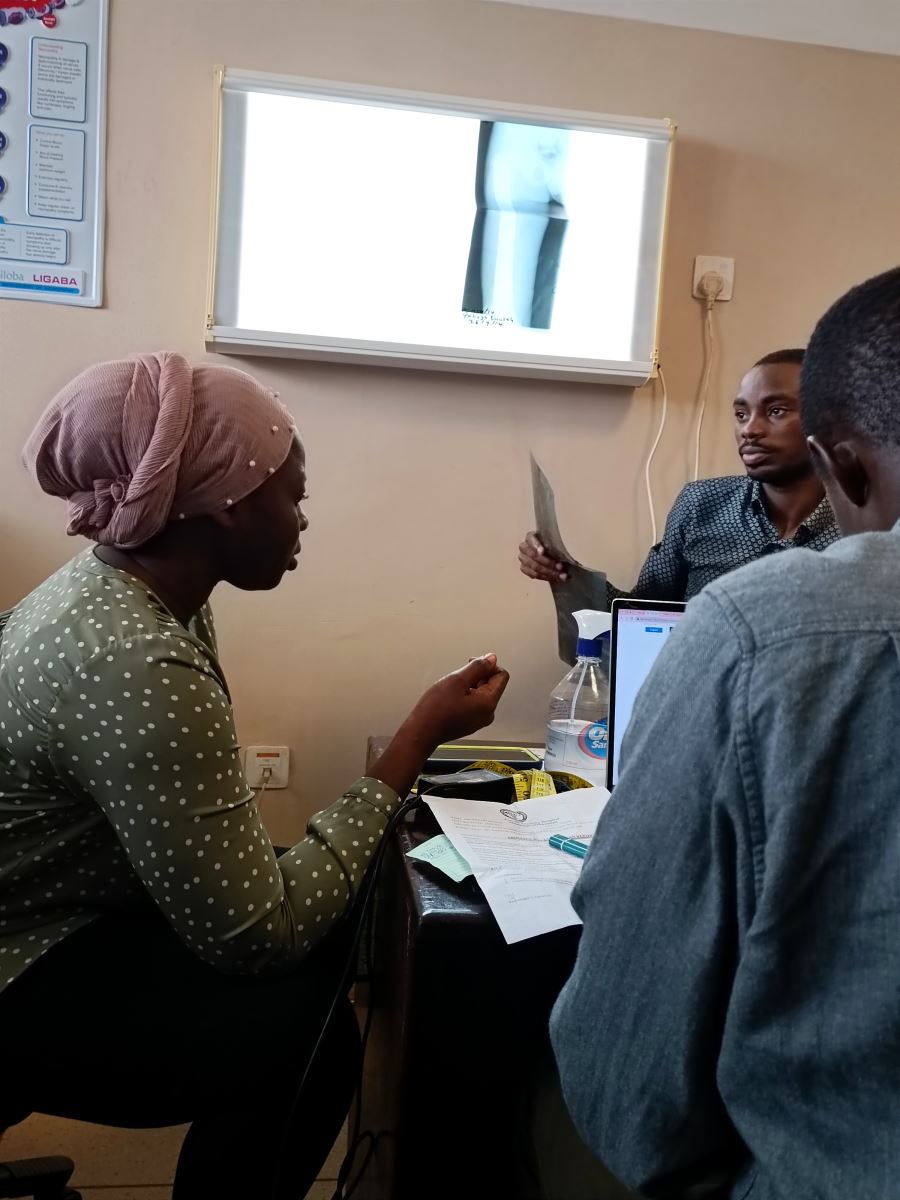

When we first visited Yahaya and did the assessment, we only had an old fracture scan. Therapy with him was challenging, as every slightest movement caused him agony. The new examination was vital, and we managed to organize and sponsor the test at a nearby hospital in Damongo. The situation was alarming from the doctors' perspective and the concerns of some of my good medical friends back home in Europe. For this reason, we urgently arranged for Yahaya to visit an orthopedist at Tamale Teaching Hospital, 3 hour's drive from Larabanga.

Confined in a cramped, stuffy doctor's office and looking at the scan, the nurse mumbled words we didn't want to hear over the voices of the 15 people crowded in. Amputation. The doctor was shocked by the extent of the bone infection when we pointed out the ankylosis between the hip and femur. The head of the femur was glued to the hip socket so that it was clear that even minimal mobility was impossible and excruciatingly painful for this young man.

That day, our persistence and patience resulted in us getting a surgery date in less than two weeks.

This would be the first operation meant to clean the abscess from the bone infection. Once that clears entirely, a hip replacement surgery would follow, although in a year. Insurance in Ghana would cover the first surgery, but all the medical supplies needed, even basic things like gloves, had to be bought with at least two blood donors before the surgery could occur. The cost of all these items (catheter, sterile gauze, surgical gloves, intravenous fluid, disinfectant fluid, morphine, etc.) totaled approximately 180 euros. The cost was insignificant to us "privileged white Europeans," but it is a cost that the locals rarely can afford.

Like most people we met in the village who survived only on carbohydrates, Yahaya's body lacked protein, and his blood results were shocking.

In addition, we provided him with crutches, which were donated to us by our wonderful friends from Croatia and Slovenia. He has been sleeping on the floor, which was quite tricky given his condition, so we found and supported a local carpenter to make him a bed so he could rest and stand up.

A few days before Yahaya arrived at the hospital for admission and most of the group members were leaving Ghana, we still didn't have the blood donor for the operation. His mother and our mentor, Isaac, didn't pass the donor screening. As it often happens, due to nutritional issues, people's hemoglobin level is too low to pass the screening. I got in touch with the Ghana National Blood Service in Accra while Isaac, on the other hand, tried finding people we could pay to give blood (which is illegal ), but the only way people are prepared to donate the much-needed blood. Simultaneously working on all fronts as a team, I got a positive response for blood replacement, and we were on our way to donate minutes before most of the volunteers were catching a flight back to Europe!

I remained in Ghana with one of them, returning to Tamale to follow up on the surgery. The surgery went well, and a few days later, Yahaya was already in the hands of physiotherapist Martin, with whom we exchanged some knowledge and views on physiotherapy practices. Two weeks later, we received the blood and bone sample results so that a specific antibiotic would be prescribed for the osteomyelitis. Yahaya could be released to home care. He is not in pain anymore, which is a success, but we still follow up on his medicine intake and adequate wound dressing before he returns for a hospital check-up.

We encountered more cases worth mentioning, but this one has had the most emotional impact on us. It helped us understand how culture and socio-economic conditions affect the quality of someone's life while in desperate need of proper health care. We have learned to operate without appropriate equipment and rely solely on manual techniques to relieve pain and discomfort. Above all, there were 5 of us with different levels of knowledge and experience, and we relied on and supported each other as a team.